- Structure of AES

- [[#Structure of AES#

SubBytes|SubBytes]] - [[#Structure of AES#

ShiftRows|ShiftRows]] - [[#Structure of AES#

MixColumns|MixColumns]]

- [[#Structure of AES#

Every block cipher performs so called “keyed permutations”, meaning the the operations of text encryption map uniquely an input block to a single output block. This property is called bijection and it is fundamental to perform the process of decryption without errors.

The term "block" just refers to a segment of the text or, more generally, any stream of a fixed number of bytes.

The key strength of a block cipher is that it leaves no hint on any aspect of the original plaintext, and in this way it makes the message basically indistinguishable from a random scrambling of random bits (in this regard, a cipher is considered insecure if there is a way for an attacker to retrieve the private key used for encryption in a way that’s faster than just bruteforcing it).

The AES cipher uses a bit long encryption key, and trying to crack it by bruteforce is basically impossible. And for this reason, algorithms such as AES-256 (using a bit long key) prove effective even against quantum-attacks (whereas public key ciphers like RSA don’t, because of Shor’s Algorithm)

Structure of AES

The basic strategy of the AES cipher to achieve a keyed permutation of the input is to perform a huge number of mixing operations on it, which are all dependent on the private key.

To start, we assume that we have a text to encrypt. The first step is to represent it as a matrix of bytes

Second step expands the key in an operation that is called “key schedule”: from the initial bit key, more keys each of length bit are derived, so that every distinct key can be applied to a different round.

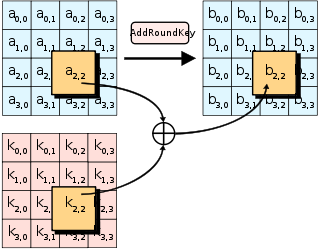

The first key’s bytes are XOR’d with the current plaintext. This step is crucial, because it provides a way to have a “keyed permutation” instead of a simple permutation.

This first XOR’d text goes then through 10 different rounds, that perform these operations:

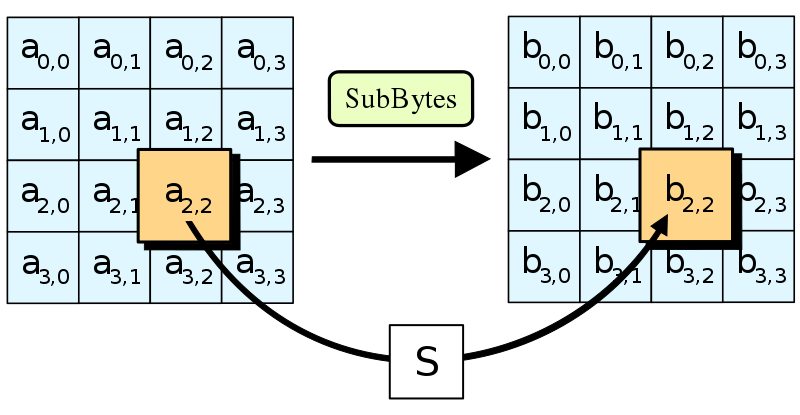

SubBytes

Each byte of the state is substituted with another byte, according to a sort of “lookup table”, called an S-Box.

In order to understand why this step is necessary, we need to take a closer look at what it means for a cipher to be really secure. Famous mathematician and cryptographer Claude Shannon stated in 1945 that for an encryption scheme to be secure it has to add as much “confusion” in the encryption process as possible. This means that the harder it is to establish a relation between the plain and ciphertext, then the more secure the cipher is. Caesar’s cipher, for example, is not secure, as the relation between the encrypted and plain text can be expressed as . Even algebraic relations, such as a polynomial in the form can be solved easily, and thus are not secure.

In order to understand why this step is necessary, we need to take a closer look at what it means for a cipher to be really secure. Famous mathematician and cryptographer Claude Shannon stated in 1945 that for an encryption scheme to be secure it has to add as much “confusion” in the encryption process as possible. This means that the harder it is to establish a relation between the plain and ciphertext, then the more secure the cipher is. Caesar’s cipher, for example, is not secure, as the relation between the encrypted and plain text can be expressed as . Even algebraic relations, such as a polynomial in the form can be solved easily, and thus are not secure.

The purpose of the S-Box is exactly to hide even more the relation between the input and the output, so that the relation function that connects the two is highly non-linear. In this sense, the process of looking up a symbol in an S-Box is expressed by a function that takes the modular inverse in the Galois field , and then applying the transformation. This can be expressed with the following polynomial:

This lookup function is calculated for each input value from to .

ShiftRows

The second step described by Shannon to obtain a valid cipher is called “diffusion”. This can be simplified as a property stating that every single bit of the input should be spread to all the bits of the output.

After the substitution operated by the S-Box we have achieved confusion, but not diffusion, because the input bit can be reversed applying the same operation to the output bit (in this case, applying the inverse S-Box), and this undermines the cipher’s security. To achieve a good level of algebraic complexity we need to alternate the substitutions with some scrambling operations (which can be reverted, however), so that each state is also influenced by the previous one. This desirable outcome in which one change in the input causes big changes in the output is called Avalanche Effect. This goal is achieved by the ShiftRows and MixColumns operations of a round.

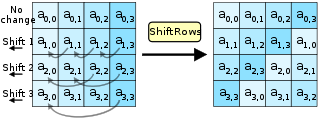

The ShiftRows operation is the simplest, and it works like this:

- The first row of the matrix is left untouched

- The second row of the matrix is shifted one position to the left, wrapping it around

- The third row of the matrix is shifted two positions to the left

- The fourth row is shifted three positions to the left

In the end, the outcome is something like this:

The goal of this simple operation is not to achieve real diffusion, but rather to make sure that each row is not encrypted independently from the others, a property that would degenerate AES into four, independent block ciphers.

The goal of this simple operation is not to achieve real diffusion, but rather to make sure that each row is not encrypted independently from the others, a property that would degenerate AES into four, independent block ciphers.

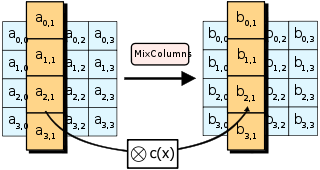

MixColumns

MixColumns is where the real diffusion happens, and that is why it is a bit complex. This operation perfoms Matrix Multiplication in Rijandel’s Galois field, between the columns of the state matrix and a preset matrix, so that each byte of each column affects each byte of the resulting column. The details are complex, but the operation can be summarized in this picture:

As a last step, the operation AddRoundKey is repeated once again.

Multiple Blocks

Up until now, we saw AES encryption with one single block of text. However, in normal circumstances it is necessary to encrypt chunks of data that occupy multiple blocks, and this is where modes of operation become necessary. These are a set of instructions on how to use the AES cipher for longer messages, and all of them introduce serious weaknesses when used incorrectly.

Keys and Passwords

All keys of an AES cipher should be made of random bytes generated with a Cryptographically-Secure pseudorandom number generator (referred to as CSPRNG), because passwords and other kinds of predictable tokens are generally easy to break.

ECB

ECB is the simplest mode of operation: each block is encrypted independently and appended to the output separately. This mode of operation is particularly vulnerable to “oracles”. Consider this ecb-oracle challenge from CryptoHack:

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

from Crypto.Util.Padding import pad, unpad

KEY = ?

FLAG = ?

@chal.route('/ecb_oracle/encrypt/<plaintext>/')

def encrypt(plaintext):

plaintext = bytes.fromhex(plaintext)

padded = pad(plaintext + FLAG.encode(), 16)

cipher = AES.new(KEY, AES.MODE_ECB)

try:

encrypted = cipher.encrypt(padded)

except ValueError as e:

return {"error": str(e)}

return {"ciphertext": encrypted.hex()}We are given the possibility to encrypt an arbitrary text which will be appended before the FLAG to constitute the final plaintext. The whole result is then padded to ensure that it is exactly 16-byte long.

The ECB mode of operation encodes the blocks as follows:

Notice how each block is encrypted separately, and since we have the possibility to append an arbitrary string to the flag before it is encrypted, our goal could be something like:

- Find the length of the flag. This will be useful later, but in order to do so we can just append one character at a time until the ciphertext doubles in size (because of the padding). Once this happens, we know that , where is the number of characters injected when , and thus .

- We can now start bruteforcing the flag one character at a time. In order to do this, we start with the first one

- First step is to obtain a block of text that contains user input for bytes, so that the last one is left as being the first character of the flag. We can do this by asking our oracle to encode, for example,

\x10 * 15. This way, our ciphertext will be in the form: where the represent the boundaries of a block, and is the string injected by the attacker. We’ll refer to the first block as , and we’ll store it for now. - Since we know that is the encryption of a text of which we know the first bytes, we can actually obtain the (that is also the first character of the flag), by simply bruteforcing all of the possible combinations of , the candidate for , by asking the server to encrypt

\x10 * 15 + cfor each possible candidate. In every case, we need to compare the first block of our output to , and once we’ll eventually find a match we know that - Reiterate step 2 for times, but inject

\x10 * (15 - i)in the first step ( is the current step of the iteration), and\x10 * (15 - i) + flag[:i] + cin the second step. If you exhaust the space for one block (which means that the flag is longer than 16 bytes), than you can simply move to an extra block (and so you will add consider15 * j - i, wherejis the current block number) The script can be found inblock_ciphers/ecb_oracle.py.

- First step is to obtain a block of text that contains user input for bytes, so that the last one is left as being the first character of the flag. We can do this by asking our oracle to encode, for example,

CBC Encryption, ECB Decryption

The CBC mode of operation adds an extra layer of confusion to the encryption scheme. Before being encrypted, each plaintext block is XOR’d with the preceding block’s ciphertext, while the first block is XOR’d with a so-called IV, or initialization vector, for short, which is usually made of random bytes. The final ciphertext is

XOR the result with the preceding block’s ciphertext, to get the relative block’s plaintext. The first block’s post-decryption part needs to be decoded with the initialization vector

Imagine now that we have a program like the following (this is taken from ecbcbcwtf):

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

KEY = ?

FLAG = ?

@chal.route('/ecbcbcwtf/decrypt/<ciphertext>/')

def decrypt(ciphertext):

ciphertext = bytes.fromhex(ciphertext)

cipher = AES.new(KEY, AES.MODE_ECB)

try:

decrypted = cipher.decrypt(ciphertext)

except ValueError as e:

return {"error": str(e)}

return {"plaintext": decrypted.hex()}

@chal.route('/ecbcbcwtf/encrypt_flag/')

def encrypt_flag():

iv = os.urandom(16)

cipher = AES.new(KEY, AES.MODE_CBC, iv)

encrypted = cipher.encrypt(FLAG.encode())

ciphertext = iv.hex() + encrypted.hex()

return {"ciphertext": ciphertext}We can get the flag encrypted via CBC, but we are only able to decrypt it via ECB.

In order to understand how to decrypt the flag with a different mode of operation, let’s try to represent the first CBC encrypted block. We could write it as:

and since the ECB decryption acts on one single block, we would get:

But since we know , because , we can get the first plaintext block by performing:

More generally, the th block of the CBC encrypted text can be written as:

Which means that retrieving the th block of plaintext is as simple as:

CBC Bit Flipping

Up until now we only saw ways to crack badly-configured samples of ECB/CBC modes of encryption, but what if our goal was, instead, to modify the plaintext so that, when decoded, it is understood as a different message?

As a sample case, consider a website that encrypts access tokens to be put inside a cookie. For example, take the flipping_cookie challenge from CryptoHack:

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

import os

from Crypto.Util.Padding import pad, unpad

from datetime import datetime, timedelta

KEY = ?

FLAG = ?

@chal.route('/flipping_cookie/check_admin/<cookie>/<iv>/')

def check_admin(cookie, iv):

cookie = bytes.fromhex(cookie)

iv = bytes.fromhex(iv)

try:

cipher = AES.new(KEY, AES.MODE_CBC, iv)

decrypted = cipher.decrypt(cookie)

unpadded = unpad(decrypted, 16)

except ValueError as e:

return {"error": str(e)}

if b"admin=True" in unpadded.split(b";"):

return {"flag": FLAG}

else:

return {"error": "Only admin can read the flag"}

@chal.route('/flipping_cookie/get_cookie/')

def get_cookie():

expires_at = (datetime.today() + timedelta(days=1)).strftime("%s")

cookie = f"admin=False;expiry={expires_at}".encode()

iv = os.urandom(16)

padded = pad(cookie, 16)

cipher = AES.new(KEY, AES.MODE_CBC, iv)

encrypted = cipher.encrypt(padded)

ciphertext = iv.hex() + encrypted.hex()

return {"cookie": ciphertext}We are given an AES-CBC encrypted cookie with a admin=False property, and our goal is to send an edited version of this token so that it is evaluated with admin=True. This should not be too complicated, because CBC lacks proper signature validation, and thus does not provide Ind-CCA security. To understand how we can exploit this vulnerability, let’s once again consider CBC’s decryption scheme:

j

j

In this case, we have full control of the ciphertext to be decrypted, as well as of the IV. We will now consider two cases:

- The red case: modifying a bit of the second block’s ciphertext results in a complete different plaintext block (because of the properties of AES), but it also modifies the bit in the same position of the next block (because of the properties of CBC). This is not really a desirable outcome, because now the second block contains garbage.

- The green case: now assume that we just want to “flip” any bit at the position of the first block. To achieve this without any undesirable outcome, we can simply edit the bit at the same position from the : this way, when performing , CBC modifies the bit desired. This outcome is desirable, because we can modify the first block as we please without any downsides

In CBC, the decryption is performed as:

Meaning that the decryption of a character in a position of the first block is:

In order for this attack to work, we assume that we know what the byte is, so that we can flip it to an arbitrary byte that we’ll call . In order to do this, we need to find a byte that, XOR’d to , turns it into : . So:

We can also extend this to work with multiple characters, as long as they are all in the first block. Let’s consider again the example from CryptoHack: we want to flip the bytes of the encrypted cookie so that, when decoded, we get admin=True. Since this is 1 byte shorter that admin=False, our goal might be to flip the bytes to something like . We can extend the formula above to work with multiple bytes:

So this means that in order to tamper the cookie, we need to XOR the part of the corresponding to the text we want to modify first with , and then with .

OFB Mode

OFB is a quasi-deprecated mode of operation that turns AES into a sort of stream cipher. The concept is very simple: take an , then encrypt it through AES standard encryption and XOR the result with the plaintext to get the ciphertext for the first block. For a block , make the same operation but encrypting not the , but the result of the encryption of the block :

OFB is the symmetrical, meaning that encrypting a text twice returns the plaintext itself.

CTR Encryption

The CTR mode of operation is an “improved” version of OFB, in the sense that it also turns AES into a sort of stream cipher, but in a more secure way.

It works by first generating a random key, called “nonce”, to which it is then appended a “counter”: this could be any value and it does not have to be generated randomly, but the key point is that it has to be different for every block. The most common approach is to start with , and then increment it for any block. This key is then encrypted with AES encryption, to be then XOR’d with the plaintext block, to produce the ciphertext:

The reason why the counter needs to be different for each block is that if it isn’t, then CTR mode is vulnerable to chosen plaintext attacks. For example, assume . Since the key is the same for each block, then also is the same for each block. That means that if we know the plaintext of the th block, then we could easily retrieve by performing:

And since does not vary, we can calculate the th block, with with:

An example is the bean counter challenge from CryptoHack:

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

KEY = ?

class StepUpCounter(object):

def __init__(self, step_up=False):

self.value = os.urandom(16).hex()

self.step = 1

self.stup = step_up

def increment(self):

if self.stup:

self.newIV = hex(int(self.value, 16) + self.step)

else:

self.newIV = hex(int(self.value, 16) - self.stup)

self.value = self.newIV[2:len(self.newIV)]

return bytes.fromhex(self.value.zfill(32))

def __repr__(self):

self.increment()

return self.value

@chal.route('/bean_counter/encrypt/')

def encrypt():

cipher = AES.new(KEY, AES.MODE_ECB)

ctr = StepUpCounter()

out = []

with open("challenge_files/bean_flag.png", 'rb') as f:

block = f.read(16)

while block:

keystream = cipher.encrypt(ctr.increment())

xored = [a^b for a, b in zip(block, keystream)]

out.append(bytes(xored).hex())

block = f.read(16)

return {"encrypted": ''.join(out)}Notice that when StepUpCounter is initialized self.stup is set as False. This means that inside the increment function the else branch will be executed, meaning that the new IV is calculated as self.newIV = hex(int(self.value, 16) - self.stup). Since self.stup is used instead of self.step, the new IV is just the old IV () that is reused for each block. Since the encrypted file is a png, we know that the first bytes correspond to the file’s header bytes, meaning we can perform a know plaintext attack as explained before.